Henry Heys, a bookkeeper, and farmer’s son from Lower Cockham, relocated with his family to Rakehead sometime between 1851 and 1861. His father, also named Henry and affectionately dubbed “Old Harry,” was renowned for his uncanny ability to estimate the precise amount of stone required for construction projects just by sight, a skill he demonstrated at Rossendale Mill, Ilex Mill, and India Mill. During a visit to discuss a new mill with Mr. Edward Hoyle and his surveyor, Old Harry, accompanied by his son Henry and Henry’s friend Richard Siddall, began surveying the site. When questioned, he confidently stated they could complete the measurements in a spare couple of hours. The surveyor, shocked, claimed it would take three weeks, but Old Harry wagered they could do it in an hour—a bet that proved accurate, despite Old Harry’s illiteracy.

Before the railway’s advent, the quarried stone was transported via horse-drawn carts, with quarrymen—known as brownbacks—using ropes and physical strength to control the heavy loads down Rakehead’s slopes. By 1869, the Heys operated out of Brandwood quarry, utilizing a mineral railway to transport stone to the main line’s sidings. Upon his death on March 28th, 1889, Henry left behind quarries in Brandwood, Facit, and Hambledon, with an estate valued at £104.2s.6d. In 1900, eleven years posthumously, Messrs Henry Heys and Sons acquired the brickworks previously owned by the County Brick & Tile Company at Rakehead.

The brickmaking facility was located across from Dove Villas, named after the dove-cotes and aviaries originally owned by Mr. James Worswick, which predated the construction of the homes. On November 4th, 1902, Henry, the son of the family, passed away at his Stacksteads bungalow in Thornton, Cleveleys, leaving behind an estate valued at £26,981.2s.1d, leading to the establishment of a limited company. The brickworks, known for providing the bricks for Ross Mill, were listed for sale in 1915. By 1917, the towering chimney, which stood at 114 feet and comprised 90,000 bricks, was taken down.

The harsh and unforgiving weather shaped the quarrymen into exceptionally resilient individuals. Despite the biting cold that would bind their hands to the stone, they maintained a stoic silence, their pride unyielding. Adverse conditions often halted work, and without labour, there was no compensation. The freshly extracted stone lay dormant, unworkable in the icy grip of winter. It wasn’t rare for these men to face temporary unemployment during prolonged frigid periods. A notable instance was in February 1895, when a brutal cold snap, deemed ‘Arctic Conditions’ by the press, forced the quarrymen of Stacksteads and Whitworth to cease work for weeks, with a meagre allowance of £1 per week from their association. Census data and personal inquiries reveal that many Stacksteads quarrymen had Irish roots, predominantly residing in Taylor Holme, Sandholes Row (now Bankfield Street), Huttock End, and the Blackwood Road vicinity.

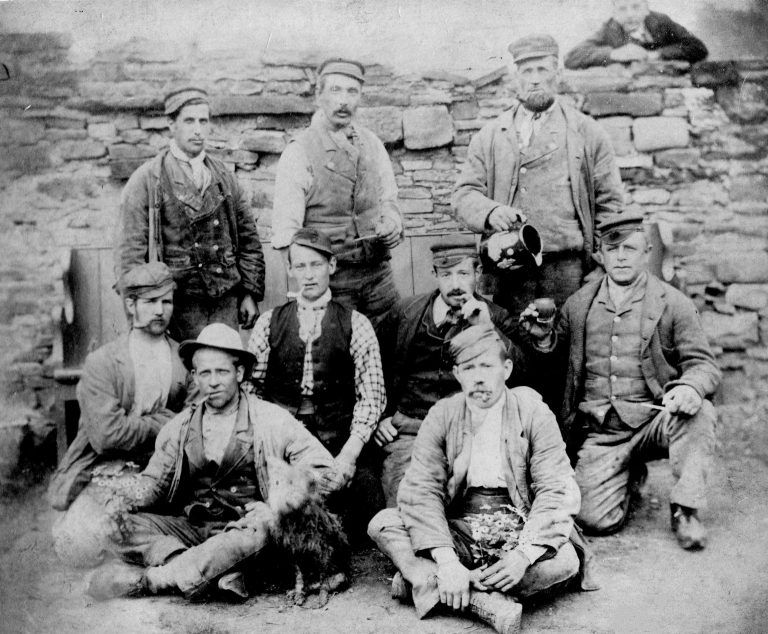

A typical Brownback’s attire as pictured below consisted of thick corduroy trousers, secured just below the knee with string to maintain a baggy fit for ease of bending. They wore sturdy clogs or hobnailed boots, a tie around the neck without a collar, and a heavy jacket for protection